Murray Hunter’s ordeal is not a distant legal footnote. It’s a vivid warning shot, cross-border censorship has moved from shady backroom diplomacy to open judicial cooperation and the price may be freedom itself.

Hunter, an Australian journalist based in southern Thailand, was arrested at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport on 29 September under a criminal defamation charge filed in Thailand but sparked, as he insists, by Malaysia. The crime? Four Substack essays in which he crucified the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) for overreach, political bias, and silencing dissent. He was released on bail; his passport confiscated, and now faces a trial beginning on 22 December

Let that sink in, Hunter was NOT arrested in Malaysia. He's NOT tried in Malaysia. He was arrested in Thailand for criticizing a Malaysian regulator. This isn’t merely an attack on one man; it’s an alarming expansion of oppression across borders and a blueprint that other authoritarian-leaning governments could replicate at will.

There’s a name for this, transnational repression. Rights groups and UN observers have long sounded the alarm. Hunter himself describes this as a kind of Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation SLAPP, in other words where governments weaponize legal systems abroad to shut down critics. In his case, the MCMC filed police reports not only in Malaysia but in Thailand as well and even initiated a civil suit in a Malaysian court that ruled against him in his absence.

Consider the implications. If a communications regulator in one country can issue a complaint that leads to your arrest in another, then journalists are no longer safe in their own homes or even on their way to the airport. As Hunter bluntly put it: “if this can happen to me … anyone … could be picked off a flight and put in a lockup.”

This is more than a slippery slope. It’s a cliff. Authoritarian crackdowns might previously have been confined within national borders; now they’re globalized, conducted through legal arms that have become proxies for silencing dissent. And the worst part? The judicial systems of ostensibly democratic or semi-democratic nations are being complicit, willingly or not.

Thailand, a country itself criticized for its own press-freedom record, has criminal defamation laws that date back decades. These laws disproportionately target critics. Hunter’s case isn’t isolated; it follows a long line of defamation cases used to muzzle opposition and scrutiny. When another state uses those provisions to go after a foreigner, things cross a dangerous boundary.

Let’s be clear, defending institutions from false and malicious claims is legitimate. Accountability matters. But when “accountability” becomes a cudgel to terrorize critics in other jurisdictions, it is no longer about reputation; it’s about control.

MCMC claims it is just protecting its “institutional integrity” and that the rule of law was followed. But context matters. In April 2024, Hunter had publicly accused the commission of acting well beyond its statutory powers, abusing its position, and collaborating with political actors to stifle free speech. He also claimed that MCMC was blocking thousands of websites, including those critical of the government, and acting like a “political Gestapo.” That is not idle lobbying, it’s fearless critique. And until we have irrefutable evidence he lied maliciously, using the force of a foreign court to criminalize him raises red flags.

Even worse, his civil defamation case in Malaysia was decided in his absence, according to Hunter. That smells of a default judgment, a strategy not unfamiliar to governments that want to make examples of dissenters without giving them a fair fight. What does that say about due process? About equal application of the law? About justice?

This should terrify journalists everywhere, regardless of geography. Because if governments can pressure or co-opt foreign legal systems to penalize critics, no one is immune. Today it’s Hunter for criticizing MCMC. Tomorrow, maybe a Turkish journalist gets arrested in Germany for mocking Erdoğan or a British writer gets indicted for lampooning the Greek Prime Minister. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the next generation of censorship.

And make no mistake, ASEAN nations have long flirted with or fully embraced, crackdowns on media freedom. But this case is something different. It is not just national censorship. It is a chilling collaboration across borders, a legal cartel against dissent.

We must call this out. Human rights groups like PEN Malaysia and the Centre for Independent Journalism have already condemned the move, calling it an overreach that undermines free expression. Yet their voices may not be enough. Journalists, activists, and democratic institutions worldwide must wake up to the fact that we're entering a new era where censorship isn’t just local, it’s a transnational apparatus.

If the international community lets this pass without protest, we are essentially giving carte blanche to governments to export their authoritarian instincts. The moral and legal fight here must be louder, more coordinated, more relentless. Free speech is not a bounded territory; it cannot be confined within borders. When it is, we begin to hollow out democracy itself.

In defending Murray Hunter, we defend not just one journalist, but the principle that dissent, criticism, and accountability are not crime, no matter where they originate. Denying that principle is not just an attack on him. It’s an assault on the idea of a free press everywhere.

If we allow foreign regulators to jail journalists in other countries for writing criticism, then we will soon find ourselves in a world where no truth teller is safe, and no voice is truly free.

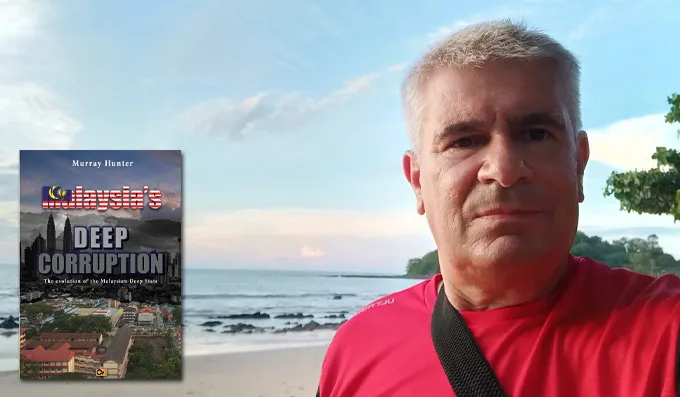

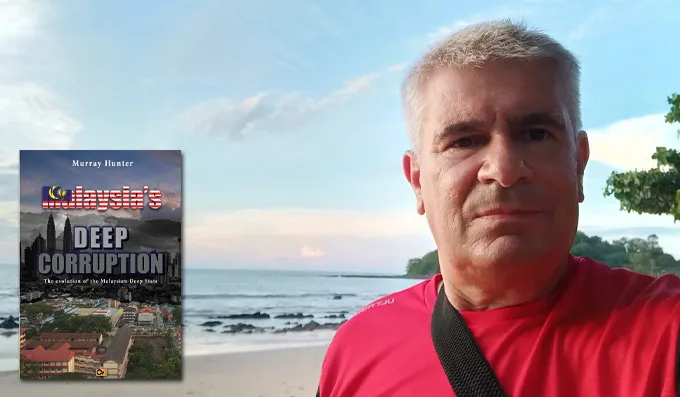

Check Murray Hunter's eBook HERE!:

No comments:

Post a Comment